The Passenger [Professione: Reporter] **** (1975, Jack Nicholson, Maria Schneider, Jenny Runacre, Ian Hendry, Steven Berkoff) – Classic Movie Review 2841

‘I used to be somebody else… but I traded myself in.’ – David Locke. Co-writer/director Michelangelo Antonioni decorates – or rather obscures – Mark Peploe’s intriguing 1975 thriller plot with a great deal of fine philosophical and ornamental work, visually as well as verbally. He called The Passenger [Professione: Reporter] (1975) his ‘most stylistically mature film’.

The wittily playful film is innovation-minded from its virtually dialogue-free opening 20 minutes to its climactic seven-minute panning shot, and is also deservedly famed for its striking location shooting by Luciano Tovoli in London, Munich, Barcelona, Algeria, Almeria and Malaga, always going for the weirdest, most artistic-looking shot possible. The images of Gaudi’s buildings in Barcelona are perhaps the most memorable, though it is fascinating also to see the shot of the Bloomsbury Centre in London around its inception.

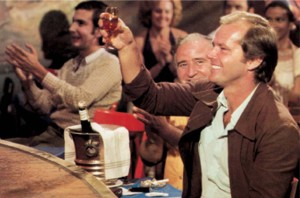

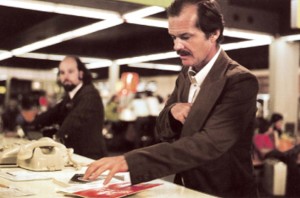

A typically intense, though underplaying Jack Nicholson brings the film into the real world as David Locke, the reporter experiencing an identity crisis on myriad European locations, not surprisingly, perhaps, since he has swapped identities with an unexpectedly deceased Briton, David Robertson (Charles [Chuck] Mulvehill), whom he finds lying on his bed after a heart attack in his hotel.

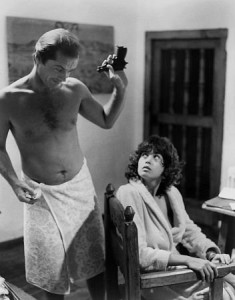

Nicholson still looks young, slim and with hair, a bit dangerous and a bit sexy. Dropping his usual Jack Show act, he seems to know exactly what to do as an Antonio hero.

While researching a documentary in the Sahara Desert, Locke meets Robertson, another guest at his Chad hotel, who after he dies suddenly turns out to have been a gunrunner. When Locke notices that the two men look vaguely alike, he assumes the dead man’s identity, transferring their photographs in their passports. He does this, apparently, to escape from his life and live a more interesting one – but he will pay for his choice.

Antonioni explains: ‘After years of work, with age, a moment arrives when there is a break in Locke’s inner armour when he feels the need for a personal revolution.’

After teasing us for nearly a couple of hours, the director rounds off the puzzle with his triumphant, elaborately staged seven-minute continuous take that serves to help to justify all of what has gone before, though the puzzle, by and large, still remains.

The film is certainly always intriguing for the energetic efforts of Antonioni and Nicholson to divert us, and there is always something to engage the attention and intellect. But, annoyingly, nobody is interested in attending to the demands of the genre they are working in, and it becomes more of a cinephiles’ niche art-house film than a high-end popular movie like the director’s similarly inclined but more accessible Blow-Up.

Certainly it is not a thriller, not a crime movie or an action-packed drama, though it has elements of all these. It is more of an existential road trip movie, with links to Antonioni’s Sixties classics La Notte, L’Avventura and L’Eclisse.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, it was a box-office flop, and proved the third and last English-language movie by Antonioni for MGM and producer Carlo Ponti, with whom he signed a deal for three English language films, beginning with Zabriskie Point (1970). Antonioni had to wait six more years to find the money to make another movie.

Also in the cast are Maria Schneider, objecting to her discreet nude scene, after having just made Last Tango in Paris (1972), Jenny Runacre as Locke’s estranged wife Rachel, Ian Hendry as the TV producer Martin Knight, Steven Berkoff, Ambrose Bia and James Campbell. None of the supporting performances is at all distinguished, leaving Nicholson to carry the movie acting-wise, which he does. Schneider is fairly hesitant, dull and unconvincing, Runacre rather over-acts, and Hendry and Berkoff do not make much of an impression, though the roles are under-written and Antonioni seems uninterested in his actors or characters, apart from Nicholson and Locke.

Antonioni said: ‘The entire story takes place in a short period of one day, from early morning until some time before sunset.’ This is puzzling because the film starts in a desert outpost in Chad, then Locke returns to London incognito, flies to Munich with Robertson’s air ticket, picks up a briefcase containing gun model illustrations from Robertson’s airport locker, is followed by two men who give him a packet of money, then, following Robertson’s diary appointments, flies to Barcelona, where he meets a French student (Maria Schneider) and continues by car through the Spanish countryside keeping the diary appointments. So, was it all a dream, or a nightmare?

Even if frustratingly messy and elusive, even shambolic, it is certainly an engrossing, fascinating film, one of great cinematic style and beauty, and a typical, quintessential work of the great Antonioni, with most of his fascinations on show.

© Derek Winnert 2015 Classic Movie Review 2841

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com